Summary:

A chance encounter at a street corner in the old town of Marrakesh, Morocco, led to an adventure where I met Eric van Hove, an internationally acclaimed artist with a vision for transforming a continent, one gleaming, beautiful, and unique electric scooter at a time…all made in Africa.

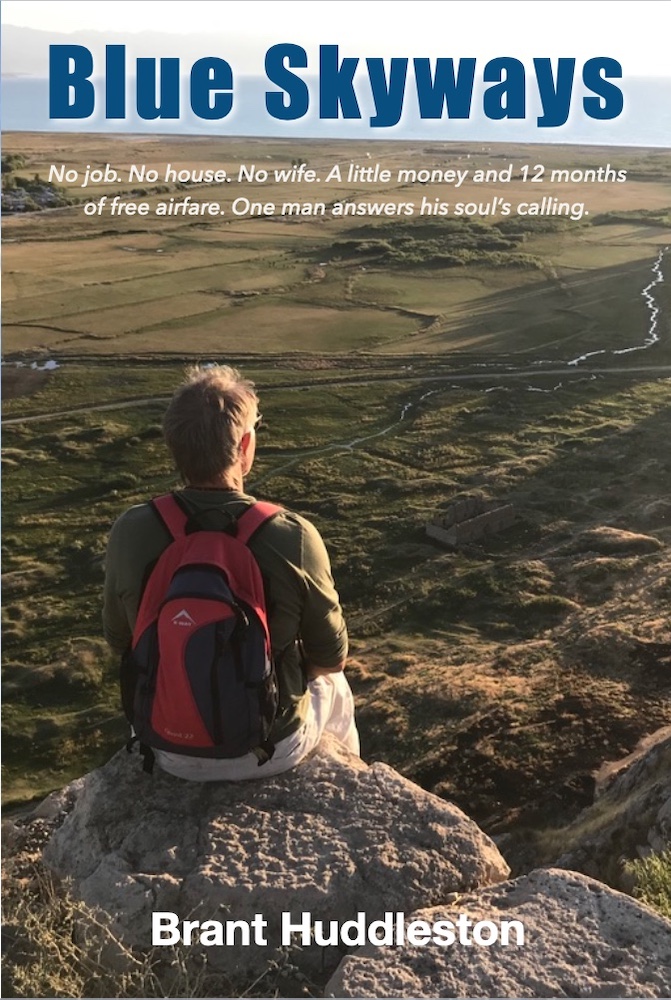

Below is a chapter from my third book Blue Skyways, available in print and audio (read by me.) Also see my photographs of the artist’s fascinating craft studio. However you experience it, I hope you enjoy the ride and that it beings you a blessing.![]()

Made in Africa

Every great achievement is the victory of a flaming heart.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

The medina of Marrakesh is a labyrinth of narrow alleys, winding through the ancient city like a maze. Massive wooden doors, many of them open to enticing, dark restaurants and eclectic shops, line the alleys. A steady torrent of motorbikes, robe-clad pedestrians, donkey-drawn carts, and hapless tourists flood the medina’s passages by day, and by night are the haunt of sallow-faced strangers, looming shadows, and anorexic cats. Every 100 meters or so, the alleys open up onto crowded markets exploding with noisy color, pungent scents, and the sounds of merchants hawking everything from football jerseys to phone batteries.

I wandered the medina for hours, often happily lost, never quite making it to my intended destinations. I was more than content during the oppressive heat of the day to sit in the shade of some hidden café, sipping mint tea with sugar, and casually watching the human circus that is Marrakesh.

Once, while trying to find a particular museum, I dared to ask a western looking woman, who appeared to know her way around, for directions. My instincts were correct — the woman was Australian and had been making her living as a tour guide in Marrakesh for eight years. I’m not sure how the subject of electric vehicles came up, but when it did, her eyes brightened.

“Oh, then you must visit the artist Eric van Hove. His studio is in the desert just outside the city. He is working there on a project involving electric scooters. Tell him I said hello,” she said while handing me her business card. I thanked the woman, took her card, and went straightaway to my hostel where I was able to find Mr. van Hove‘s website. I sent him a message requesting permission to visit.

Eric Philippe Bernard Van Hove Marsan de Mondragon, aka Eric van Hove, is a Belgian conceptual artist and entrepreneur, born in Algeria and raised in Cameroon, both countries in Africa. As an adult, Eric spent ten years living in Japan, where he received a Master’s degree in Traditional Japanese Calligraphy at the Tokyo Gakugei University, and after that a PhD degree from the Tokyo University of the Arts. It was in Japan that Eric learned to appreciate the art of copying as a means to improve one’s craft — an appreciation that would prove invaluable in his later work with scooters.

While Eric has studios in Brussels and Marrakesh, and has exhibited his art all over the world, he is highly nomadic, having made site specific works in over 100 countries. He is among the most traveled artists of his generation.

In 2012, Eric arrived in Morocco to resume work on an ambitious sculptural endeavor he had been preparing for years. He gathered around him 42 master craftsmen from the Maghreb region of Northwest Africa and began rebuilding a Mercedes 6.2L V12 engine using rural materials and centuries’ old craft techniques still found in the North African country. This work of art, eventually acquired by the Hood Museum of Art, became the cornerstone of a new chapter in Eric’s creative practice and a “renaissance of African craft.”

The more I learned about Eric and his work, the more excited I became, so I was greatly disappointed when, later that day, I received a polite but terse reply to my earlier inquiry.

“I regret that I am unable to see you this time. I am scheduled to leave for Brussels in the morning, and I need every minute of my time to prepare.”

Somewhere in the back of my walnut-sized brain, I remembered a lesson from my years of IBM sales training. I was taught that it takes an average of 28 “noes” to get to one “yes.”

“One ‘no’ down. 27 to go,” I thought, so I made my request a second time. I am not ashamed to admit that I resorted to pleading. Fortunately for me, the artist relented.

“I can give you 30 minutes,” he said, and sent me his address. In the end, Eric gave me so much more than his time. He gave me an inspiring vision for a continent.

The following day, with help from my hostel host, I rented a car and driver, who I understood was to take me all the way to Eric’s studio about an hour’s drive from the city center. Now, I know a shake down when I see one, so when the driver stopped the car at the city limit and demanded more money, I gave him the international words for “Go to hell” and got out. The treeless, barren street, far from almost anything, was baking like a furnace. My driver watched in disbelief as this obstinate American geezer walked away from the car and across the scorching highway. My eyes were set on what appeared to be a building in the distance, shimmering like a torch in the midday heat.

“A mirage?” I wondered, taking a swig from my ever-present water bottle. I started walking, leaving my driver muttering in Arabic behind me.

A half mile or so down the road I came to the building, a hotel (praise Allah), and not just any hotel, but one of the most splendorous I have ever seen. The lobby opened up like the Taj Mahal, with white columns supporting a sky-blue tiled ceiling, under which I found sparkling fountains, velvety sofas in deep purples and maroons, and green potted palms, their fronds rustling in fan induced breezes. A large turquoise pool, surrounded by a well manicured lawn, beckoned me from the vast courtyard. But alas, I was a sweltering sojourner and not a guest, so I had to turn away.

The hotel’s front desk clerk graciously put in a call on my behalf to Eric, who came to my rescue by sending a private car to pick me up. Thirty minutes later, we were bouncing down a dirt road toward a nondescript brown building – the Marrakesh studio of Eric van Hove. The artist greeted me warmly, and we retired to a second story balcony where, for the next hour, I heard Eric’s astounding vision for what he calls “The Mahjouba Initiative.”

Mahjouba is the classical Arabic name for headscarf or veil, and with an “a” at the end, makes the word distinctly female. Eric intentionally chose this name for his scooter project, not because of what veils cover, but rather for what they have the potential to reveal. Eric wants to unveil to Moroccans, and Africans in general, the potential of their craft and their capacity for self-reliance. He started his Mahjouba Initiative with a question: How can we transform not just the city, not just a nation, but a whole continent, by teaching local craft people how to make a useful product out of local materials and with indigenous skills?

This was the bold, even audacious, challenge the artist chose for The Mahjouba Initiative. Eric recognized that talented local craftspeople were on a race to the bottom of the economic hierarchy, wasting their skills making ashtrays and other useless knickknacks by the hundreds for tourists like me, while exports from China were stealing the more profitable middle tiers. Eric’s vision is to build a system whereby these same local craftsmen can manufacture a “Made in Africa” product that promises to both enhance their skills and put food on their tables. The product he chose is the electric motor bike.

Sitting on that balcony, I heard Eric expound on the intersection of art and industry, the challenges of manufacturing in an age of Chinese dominance, how the vestiges of colonialism in Africa continue to hurt the crafts, and the opportunity to build African-made, couture products for customers who want something other than a mass-produced knock-off. Since in a prior life, before IBM, I restored classic cars and spent many years busting my knuckles spinning wrenches, I am no stranger to vehicles, so I was especially interested to hear Eric comment on the Fuller car, a gleaming beauty made in Nebraska in the early 1900’s, when making cars by hand was still standard practice.

By the end of our talk, I was beginning to catch Eric’s vision for a continent wide socioeconomic revolution, sparked to life by the power of private industry, the artist’s soul, entrepreneurial grit, and perhaps a bit of help from the King of Morocco, who received as a gift one of Eric’s handmade scooters.

“Would you like to see the shop?” Eric finally asked me, stubbing out his third cigarette.

“For sure!” I said, jumping up. He led me downstairs to where a half dozen Moroccan men were fashioning gearboxes, chassis, saddles, and other scooter parts out of whatever materials were available to them – wood, bone, copper, steel, porcelain, and plastic. Over the din of hydraulic tools and the bright blaze of acetylene torches, Eric explained how each man, an artist as well as a craftsperson, customizes the part with his own design so that it is not only functional, but also beautiful.

“For sure!” I said, jumping up. He led me downstairs to where a half dozen Moroccan men were fashioning gearboxes, chassis, saddles, and other scooter parts out of whatever materials were available to them – wood, bone, copper, steel, porcelain, and plastic. Over the din of hydraulic tools and the bright blaze of acetylene torches, Eric explained how each man, an artist as well as a craftsperson, customizes the part with his own design so that it is not only functional, but also beautiful.

“In this way,” he said, “it is quite possible for the customer to buy an electric scooter that is as unique as they are, but still at a very affordable price.”

Rideable art, but not fragile art, mind you. Eric is collaborating with the Dartmouth College’s Thayer School of Engineering to ensure his product, as beautiful as they will be, stands up to the rigors of the road.

“As you can see everywhere in Africa,” he said, “scooters are the workhorses of the people. Scooters from The Mahjouba Motor Company must be strong enough, and safe enough, to carry whole families of three or even four people, or to be used as a wagon for carrying goods.”

As I walked through the shop, I was reminded of how creative people all over the world make, or remake, products to be “one of a kind.” The mechanically inclined might “chop” a car and give it a trick paint job until it is unique. Other creators might tear apart a garment and sew it back together again with colorful new pieces until it can be found nowhere else but on them. Unlike the animal kingdom, humans enjoy looking differently from one another, and Eric’s business and production model will, eventually, allow people to buy a safe, utilitarian, but still totally unique electric motorcycle “made in Africa” by the skilled hands of local craft people. His model really could transform the continent, and I left Eric with sincere best wishes for success and a promise to tell his story as best I can.

There is a line from the Old Testament that says, ”Without a vision, the people perish.” We often look to politicians for such a vision, and we are often disappointed by how shallow they are. I submit that if we truly want a bold vision, a strategic vision, the kind of vision that will shift the earth on its axis and show us where we can be in 100, 500, or even 1,000 years, then we need to pass over the politicians and look to our artists, people like Eric Philippe Bernard Van Hove Marsan de Mondragon, who will transform a continent, one gleaming, beautiful, and unique electric scooter at a time…Made in Africa.

Books by Brant

Most Recent

For Christmas 2018, my brother, a pilot with American Airlines, gave me a gift that became the experience of a lifetime: 12 months of free travel anywhere American Airlines flies.

Thus began a year long journey that took me from the rocky coasts of Portugal, to the hot sands of Morocco, to the mangrove swamps of Panama, with many places beyond and between. In cheap hostels and the backwaters of the nomadic milieu, I discovered a treasure chest of colorful and fascinating people. I tell their stories and a bit of my own.

The trip became as much a spiritual and emotional journey inward as it was a literal outward one, and found me in a place those of you who are in the second half of life are likely to recognize.

With references to the philosophies of Carl Gustav Jung, Jesus, Bob Dylan, and the Buddha, Blue Skyways is an international romp by a man in his 60’s with not much more than a pack on his back, and still much to learn.

A suspense/thriller novel!

When a psychology doctoral student Brian Drecker uses advanced software to analyze dreams from around the world, he discovers odd patterns that cannot be explained. Where one person's dream ends, another's begins. Unique objects appear again and again...even though the dreamers are complete strangers.

Drecker discovers the patterns form a map pointing to an ancient, lost object. Soon after, he is mysteriously murdered, leading his deadbeat brother and estranged wife on an international race to find the treasure, and the murderer. Along the way, the troubled couple are opposed by dark forces of the religious underworld, who launch a global pandemic to ensure the map of dream's secret remains lost forever.