The Lost Possum: My Father the Spy and How I Found Him

Introduction:

For over 30 years, I lived in Richmond, Virginia. I raised my three children in the city’s mostly white suburbs. After they were grown and I was first divorced, I moved into the heart of the city, which was then, and may still be, largely populated by African/Americans. I enjoyed some of the happiest years of my life there, and still consider Richmond “home” even as I now gallivant around the world and enjoy the life of an aging flâneur.

Richmond was once the capitol of the Confederate States of America, and a place where tens of thousands of African men, women, and children were sold into slavery. The city’s soil holds the bodies, and the tears, of the enslaved, as well as those who enslaved them. Richmond was, therefore, understandably the target of Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests during the tumultuous election year of 2020, resulting in some of the pictures I took below.

In the Spring of 2020, I was living in a rented house in a multiracial neighborhood, walking distance from where these pictures were taken. Every night I heard the police plane flying overhead, and the sirens wailing from dusk till dawn. I was worried, as were my neighbors, that the riots would spill over onto our street. We were all on edge. Large, equestrian statues of Confederate heroes like Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson that once stood prominently along Richmond’s leafy Monument Avenue were a particular focus of BLM scorn.

Although I generally don’t agree with violence as a means of achieving an end, I could understand why some despised these monuments. What I could not understand was why BLM rioters also destroyed small business and charity outlets, set buses on fire, taunted police, and pretty much terrorized the city. It occurred to me then that something more might be going on. As a way of exploring my own feelings and evolving opinions, I wrote the essay you’ll find below, called The Lost Possum.

A few years have gone by since those scary days in Richmond. The fires in the city have gone out, the Confederate statues have been toppled, and I moved away to a far off land. But the core idea I wrote about in 2020 stuck with me. As a new war in Ukraine rages, I believe I see Ariadne’s “red thread,” one leading into the Minotaur’s labyrinth where we encounter the monstrous forces that shaped how men raised in the 20th century think and show up in the world, men like Trump, Putin, and me.

That red thread led me to look back at my childhood, and to look within, challenging my own bigotry, and facing, with knees knocking, the black, murky, and oft miasmic depths of my own personal labyrinth. My journey into the maze, still underway, forced me to encounter and wrestle with the biggest ghost any man has in his life…that of one’s own father.

I am writing about my short life with dad as a way of exploring my own ragged evolution as a man, in the hope that it may help others find and follow their own Ariadne’s thread out of their own labyrinth, and maybe, just maybe, shed some light on why things are the way they are. The result is a new book in progress called The Lost Possum: My Father the Spy and How I Found Him, the introduction and a few chapters of which you’ll find below.

If you want to keep up with the book’s progress, I encourage you to sign up for my newsletter. Thanks for your interest, and enjoy a few parts of The Lost Possum.

Prologue to the Book in Progress

Some of you will remember a scene from the 1980 Star Wars film The Empire Strikes Back where the Jedi master Yoda leads his knight-in-training Luke Skywalker to the dark opening of a spooky cave.

“In you must go,” commanded Yoda.

“What’s in there?” Luke asked, peering warily into the ominous hole.

“Only what you take with you,” Yoda said.

Luke Skywalker steps into the cave and encounters his greatest fear — the black clad, towering figure of his arch-nemesis Darth Vader. Skywalker cuts off Vader’s head, only to discover his own face inside the smoking helmet. The young knight is taking the first painful step of learning who he is, and of his relation to Vader. “We have met the enemy, and he is us,” said the philosopher possum Pogo.

That scene, and in fact much of the Star Wars saga, is based on the work of Joseph Campbell, an American professor of literature and author of The Hero with a Thousand Faces. In that book, Campbell deconstructs the journey of the archetypal hero as shared by world mythologies. The well-worn path Campbell identified has been trod by every hero from Odysseus to Skywalker, and while we don’t always recognize it as such, it is your hero’s journey, and mine too.

Eventually, for all men, there comes a time and place on that journey where we must encounter the man who loomed large in our psyche, our fathers. For men like me (and Luke Skywalker,) who desperately do not want to be anything like the man who sired us, that encounter can be a dark one indeed, exposing our “shadow side” in ways that can be downright scary.

What can we do then when we encounter our fathers in the dark cave and see our own image reflected in him? Joseph Campbell offered an answer. He said: “The work of the hero is to slay the tenacious aspect of the father (dragon, tester, ogre king) and release from its ban the vital energies that will feed the universe.”

Feeding the universe is no small task. It’s not for the timid. But for the few of us who dare to enter the cave, we may just discover the hero within, the one who can, in his own small but important way, make the world just a little bit better. This book is for anyone of any gender who wants to be part of that noble mission.

In these pages I share my experience as one who came to manhood in the late 1950’s and 60’s, a time when my country, the United States, was in crisis. Political assassinations, an aimless war, race riots, civil unrest, the sexual revolution, hippies, rock&roll, feminism…these were all agents of change common to that time; agents that affected how men like me show up in the world.

And honestly, we don’t always show up well. I believe many of today’s woes, from gun violence to domestic abuse to climate change, have their root cause in men’s health, which I submit is presently not good, nor has it been for some time. There are no excuses for negative male behavior, but there are reasons for it, and they must be examined if men are to be healthy participants in a world that desperately needs them.

Being a healthy male means more than just having a working set of balls and a penis; it means being endowed with a powerful male essence and energy that naturally motivates men to, as men’s coach Corey Wayne said: “Take risks, penetrate through obstacles, and push toward our goals with purpose, drive, and mission.” It means stepping up, even when we don’t want to, or when we are afraid. “The cave you fear to enter,” said Joseph Campbell, “holds the treasure that you seek.” So in the words of Master Yoda: In you must go.

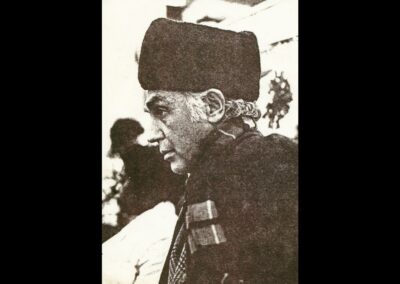

Before I close this introduction to The Lost Possum, a title which will be explained in the body of the book, I want to touch on the small matter of my father the spy. I don’t know for sure that dad was a spy, but there are plenty of suspicious clues suggesting he was working for the CIA, not the least of which are all the years he spent in the wrong places at the right times — East Berlin during the cold war, Iran just before the Shah fell, secretive Army labs in the U.S. desert, communist Yugoslavia in the dead of night, and other such inexplicable episodes.

As a child, I was always told dad was a “consultant to the military,” but in later years, I started to question that explanation. For this book, I dug into my father’s story in ways I never thought I would, for I was estranged from him while he was alive. There’s really no excuse for that, but there are reasons, starting with the fact that dad did not reveal much about himself, a practice all too common for men, who as psychologist James Hollis said, generally participate in a “conspiracy of silence.” It wasn’t until twenty years after dad died that I began to piece together his life, and in doing so, I began to piece together my own as well.

Our story begins late one night in 2011, when my phone rang, opening the door to a secret room in my father’s life, and a forbidden love that was as bitter as it was sweet.

Chapter One: The Phone Call

She said her name was Beth Richards, and then she started to cry. It was a name I had heard all my life, but always through the gritted teeth of my mother, for Beth was my father’s lover for over 20 years.

I never expected to meet Beth except for a conversation I had with a date. I was in my early 50s and newly divorced. Dad had been dead for years. My date and I were just getting to know each other when the woman, a practicing psychotherapist, said: “Tell me about your father.”

“I don’t know,” I said. “There’s not much to tell. He was kind of an asshole.”

Now one doesn’t say such a thing to a licensed clinical social worker with a masters degree in psychology and expect to get away with it scott free. My evasive response threw all kinds of yellow alert flags in my date’s head, and she was not shy about probing further. They don’t call professionals like her “shrinks” for nothing – they are skilled at getting inside your head and understanding why you are what you are.

“Why was he an asshole?” she asked.

“He hurt my mother.”

“How did he hurt your mother?”

I then relayed the only bit I knew about my father‘s affair and how, when I was about six years old, dad emotionally checked out of his family, showing up only as an angry disciplinarian (“I’ll bang your heads together,” he was infamous for saying), militant critic (“Stand up straight!” I heard too many times to count,) and financial provider (he put me and my five siblings through college and generously helped us buy our first houses).

“You need to find her.”

“Who?” I said.

“Beth,” my date said. “Beth Richards.”

“Why the hell would I want to do that?” I said.

“Because she knows a side of your father that your mother does not know. She knows a different version of your dad’s story than the one you’ve been told.”

“I don’t know,” I said, rubbing my chin.

“Don’t you want to know your father? I mean, really know him?”

“I guess so. I don’t know. Let me think about it.”

I did think about it. I thought about how he made mom cry, how much she hated him, and more than that, I thought about how much I hated him, how it felt to grow up without him. I thought about all the times I needed him, to help me learn how to fish, or fly a model airplane, shoot a basketball, or write a college entrance exam, and how he wasn’t there for me. I thought about how we fought, sometimes with fists.

But I also thought about how he had been there, in my earliest years, teaching me how to sail, how to hunt for crabs in Maryland’s Severn River with bologna tied to a string, how to shoot a 22 calibre rifle, and how to paint the house he and mom built by themselves, brick by brick. More importantly, he showed me how to take risks, gave me a love of travel and adventure, and taught me how to navigate a complex, changing world. He demonstrated how to be a man, and how not to be one, in ways I have only recently begun to appreciate.

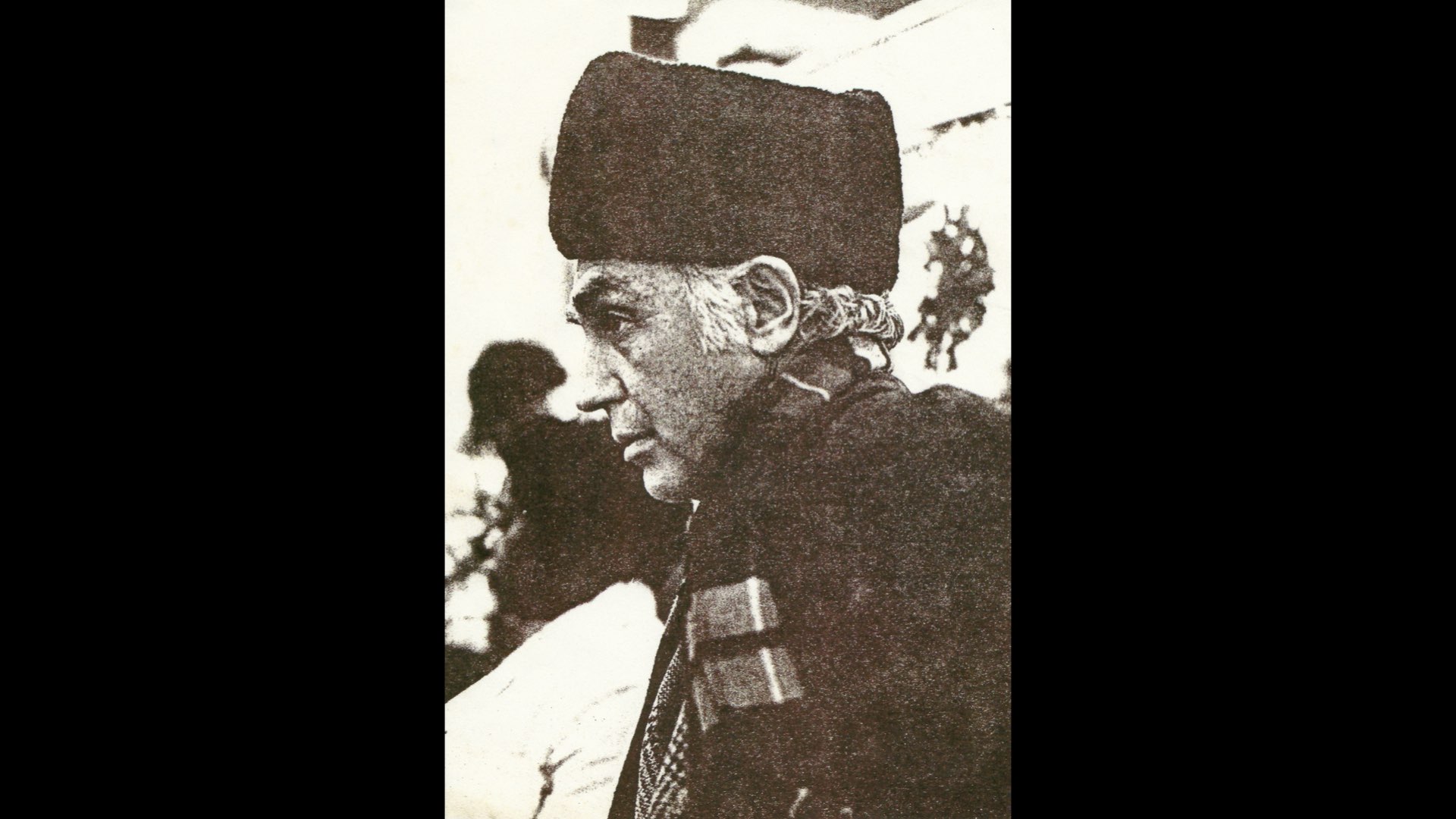

***

Dad was six feet tall with a muscular build as lean as an Olympic swimmer. His pale blue eyes belied his northern Italian heritage, and although he was balding, his hair was silver for as long as I could remember, giving him the appearance of an aging Sean Connery. While he rarely smiled at home, I see his grin in pictures, and it is positively 100 Watt, brilliant and charming. He wore only one piece of jewelry, a gold class ring awarded to him upon his graduation in 1942 from the vaunted Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). There he earned a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering, later earning a Master’s degree, and enough credits to be just shy of a PhD.

I remember seeing the image of a beaver on that ring, and it wasn’t until I earned my own degree in engineering that I realized how hard it must have been for dad, as he was the son of a Boston milkman who had little appreciation for dad’s “bookishness.” While dad did not inherit his father’s simple, backslapping, easy going style, dad did gain grandpa’s Boston accent, one common to all my relatives from that side of the family, and one which, to this day, sounds familiar to my ear.

Dad wasn’t so bookish as to dodge the army. He joined in 1941, interrupting his education for three years. He left the service after the war with a limp and a future spot in Arlington Cemetary, where his ashes are today.

Those early years with dad, in the late 1950s and early 60s, were filled with the best of everything – a pedal powered train on a track in the backyard, summer vacations at Rehobeth beach, where I got my first taste of cotton candy plucked from a pink plume as big as a woman’s beehive hairdo; an electric monorail I would give my eyeteeth to still have today; an appearance on the Bozo the Clown TV show that dad arranged, a float through Florida’s everglades in a glass bottomed boat, and so much more.

Our first house abounded with dad’s toys, reflections of his diverse interests — a guitar, a black grand piano, tennis rackets, Raleigh 10 speed bikes, a gas powered model airplane, stacks of Playboy magazines, a Brownie 8 mm camera with film splicing equipment, golf clubs, Heathkit radios dad built, the best stereo money could buy, two sailboats, and tools of all kinds.

Dad grew a huge garden full of corn, asparagus, lettuce, and bright red and white radishes he ate raw with salt, the same way I eat them now. He bought a new car every other year, including a 1955 teal green and white Chevrolet Bel Air convertible he flipped, giving him a scar under his chin; a bronze 1960 Chevy Impala with tail-fins as wide as the flying nun’s headgear; a 1962 Chevy Corvair my mom drove and into which, to the astonishment of my friends during a visit to the National Zoo in Washington DC, she packed our picnic basket in the front trunk (Corvair engines were in the rear); and finally, my favorite, a 1960 turquoise and white Nash Metropolitan, which reflected dad’s appreciation for fuel efficient compact cars.

That brick rambler overlooking the Severn River in Maryland was full of wonderful things…and an attentive father. Then, about 1964, not long after Sputnik, the Cuban missile crisis, the JFK assassination, and during the deep freeze of America’s cold war with the Soviet Union, dad faded from my life.

I would not have given dad or any of his things a second thought except for my conversation with the psychotherapist, but she provoked an interest. What if dad really wasn’t who I thought he was? I wondered. What if he cared for me in ways he couldn’t express? What if there really is a part of the man my mom and I don’t know?

I decided to find out. I hired a private investigator who provided all known addresses for Beth Richards. Ten looked promising, so in 2010 I wrote up ten identical letters expressing my interest in meeting her and sent them off, just like throwing bottles into the ocean and hoping someone finds just one with a dry letter inside.

Late one night a year later, when I had nearly forgotten the effort, my phone rang.

“Hello Brant. This is Beth Richards.”

And then she started to cry.

###

The Lost Possum: The Original Essay

Duris dura franguntur.

(Hard things are broken by hard things.)

It is impossible to separate male essence from western civilization, as the former has been shaping the latter for eons, both having been influenced by a powerful Greco/Roman patriarchy that deeded modern men with a crippling modus for how we show up in the world. That is, we tend to view the world entirely by the gray matter between our ears (a Greek philosophical tendency) and value ourselves entirely by our economic output, proven or potential (a white Anglo-Saxon Protestant tendency).

What’s missing, as the Divine Feminine can teach us, providing we men are willing to listen, is less about what we accomplish (“accomplishments” as the pièce de résistance of the modern resumé) and more to do with how we synthesize our feelings and experiences, those being core ingredients of “wisdom” (no section for that on the resumé yet). True wisdom requires the integration of mind, body and soul, and a healthy man is in touch with all of these parts of his being.

As Dr. Anita Johnston explains in her book Eating by the Light of the Moon, when we men detach from our bodies, as we often do, we also detach from the earth body, which has its own cycles. This is one reason why men, Dr. Johnston says, who have historically wielded power, tend to run roughshod over the environment. We men are more likely to view the natural earth as something to be conquered and subdued rather than loved and nurtured. This is a spiritually impoverished world view, but until recently, a pervasive one.

The Male Warrior Class

The detached, impoverished male world view is not entirely men’s fault. To some extent, perhaps a large extent, men are bred to be detached. We are raised with admonishments such as “big boys don’t cry” and, if we do cry, to “man up.” We are told we are made of dirt and animal parts, while girls are made of “sugar and spice and everything nice.” Our heroes are muscular supermen who are brave and unflinching, who sacrifice all for God, country, Queen, or whatever cause happens to be flaming up at the moment.

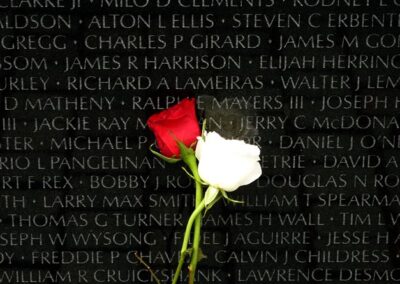

As a young man, with WWII looming behind me and the Vietnam War looming ahead, I understood my role to be cannon fodder, that is, one of those who launch into ferocious battle at the sound of a bugle…one of those needed to fight and die in order to preserve life, liberty and the American way. This mindset, however radical it may seem now, serves a valuable purpose. Western civilization, or any civilization for that matter, would not thrive without its warrior class, and the warrior class has, until recently, overwhelmingly been made up of men.

The so-called “long peace” of the late 20th and early 21st centuries (that is, the longest running period of history without a major war) has been good for mankind but devastating for men, who, like animals whose natural habitat has been destroyed, increasingly find themselves out of place, out of their element, in a strange and changing world where nothing works the way it used to, that is (by some men’s reasoning), the way it’s supposed to. The typical male’s most innate and valuable skill, that as valiant defender and slayer of dragons, is suddenly without cause, without purpose. The fierce warrior energy, so common to males, is now all bottled up with no place to go other than sports or business, the modern proxies for war.

Lost Men

If those two outlets fail to relieve, then the displaced animal, with his natural warrior energy converted into rage and confusion inside the pressure cooker of denial, finds an unhealthy way to relieve himself. As poet Robert Bly said in his book Iron John: A Book About Men:

If a culture does not deal with the warrior energy — take it in consciously, discipline it, honor it — it will turn up outside in the form of street gangs, wife-beating, drug violence, brutality to children, and aimless murder.

That tragic man, the displaced warrior, is like a possum whose home has been destroyed to make room for a suburban subdivision. It wanders the city streets and sidewalks, completely out of its natural habitat, foraging for food in dumpsters, and engaging in unnatural behavior that will eventually kill it. This is why, whenever I hear news of yet another school shooting, I don’t even need to ask — the shooter will have a penis. A diseased and misplaced possum bites.

Survival options for 21st-century men are hard to find. Author David Deida, in his book The Way of the Superior Man: A Spiritual Guide to Mastering the Challenges of Women, Work, and Sexual Desire, has done a good job of describing a beautiful way for men to regain their place in the new world. Deida says:

This newly evolving man is not a scared bully, posturing like some King Kong in charge of the universe. Nor is he a new age wimp, all spineless, smiley, and starry-eyed. He has embraced both his inner masculine and feminine, and he no longer holds onto either of them. He doesn’t need to be right all the time, nor does he need to be always safe, cooperative, and sharing, like an androgynous Mr. Nice Guy. He simply lives from his deepest core, fearlessly giving his gifts, feeling through the fleeting moment into the openness of existence, totally committed to magnifying love.

Deida wrote those words in 1997, long before the era of Trump or the emasculating effects of the #metoo movement.

Donald Trump

Many saw the rise of Trump as the rise of latent fascism in America, the so-called “alt-right” flexing its ugly muscles. That is, many saw Trump as a political movement requiring a political response.

I see it differently. Trump was elected in a wayward sexual revolution, not just a political one. People of all genders are scrambling to figure out how a healthy male should show up in a rapidly changing 21st-century world, a world where men have precious few good role models to follow.

Trump is Deida’s “scared bully,” the King Kong who first frightens people and then offers to protect them…at a price. Watch any episode of PBS’ The Dictator’s Playbook and you’ll see Trump’s tactics are a proven way to manipulate people, so it is no surprise that a hundred million Americans are drawn to him. “Trump will save us,” they say, attracted to his take-no-prisoners machismo, swagger, and bold bravado. He is an orange Mussolini.

But Trump is also, in part, a pendulum swing reaction to the other, unhealthy male role model that gained ground under Obama, one that continues to be hammered home by #metoo radicals, that of Deida’s “starry eyed, New Age wimp…the androgynous Mr. Nice Guy.” This guy is not really nice at all. He has unconsciously adopted a form of self-loathing in a vain effort to appease women. He has unconsciously absorbed the “Men are pigs” message I regularly heard from feminists as a teenage boy in the 1970’s, feebly allowing his natural masculine essence to be slapped away so he can “discover his feminine side” (the message I heard in the ensuing 30 years).

That was my generation. Millennials and GenX males are under even greater condemnation, trying to survive in a world where white males occupy the lowest rung in the social ladder, and any one of Facebook’s 52 other genders (yes, there are 52) are above him. I can’t even imagine the pressure they feel to conform, and many do…unnaturally. I see them everywhere when I visit Richmond today. Lost possums, they are.

That was my generation. Millennials and GenX males are under even greater condemnation, trying to survive in a world where white males occupy the lowest rung in the social ladder, and any one of Facebook’s 52 other genders (yes, there are 52) are above him. I can’t even imagine the pressure they feel to conform, and many do…unnaturally. I see them everywhere when I visit Richmond today. Lost possums, they are.

I believe that in the years leading up to the election of 2016, Americans took a look at a few of those confused creatures on university campuses, or worse, looked at them across the dinner table, and said to themselves, “Something has gone wrong and we need to fix it.” They are right to think that way: modern men are in trouble, and their situation is getting worse, to the bane of everyone.

The Way Out

Finding Deida’s “way of the superior man” is not easy. It’s as challenging as finding Jesus’ narrow path to salvation. “Few are they that find it,” Jesus said.* Although I actively seek that superior way, I have yet to fully find it, but I never give up trying. I have found it takes a good bit of personal rewiring, hard work, and a shitload of mistakes along the way.

Such is the path of progress.

###

* Author Corey Wayne says that only three percent of men do the hard work to achieve the level of awareness needed to be truly superior men, hence the name of his book: How to Be a 3% Man.

Further Reading About Men

Highly recommended:

- Fire in the Belly: On Being a Man by Sam Keen

- The Way of the Superior Man: : A Spiritual Guide to Mastering the Challenges of Women, Work, and Sexual Desire by David Deide

- Iron John: A Book about Men by Robert Bly

- No More Mr. Nice Guy: A Proven Plan for Getting What You Want in Love, Sex, and Life by Dr. Robert Glover

- The 3% Man: Winning the Heart of the Woman of Your Dreams by Corey Wayne

Also good:

- Wild at Heart: Discovering the Secret of a Man's Soul by John Eldredge (a christian oriented book)

- Under Saturn’s Shadow: The Wounding and Healing of Men by James Hollis, PhD (I love Hollis but be forewarned: This is thick reading lush with Jungian psychology)

My Own Essays On or About Men:

Books by Brant

Most Recent

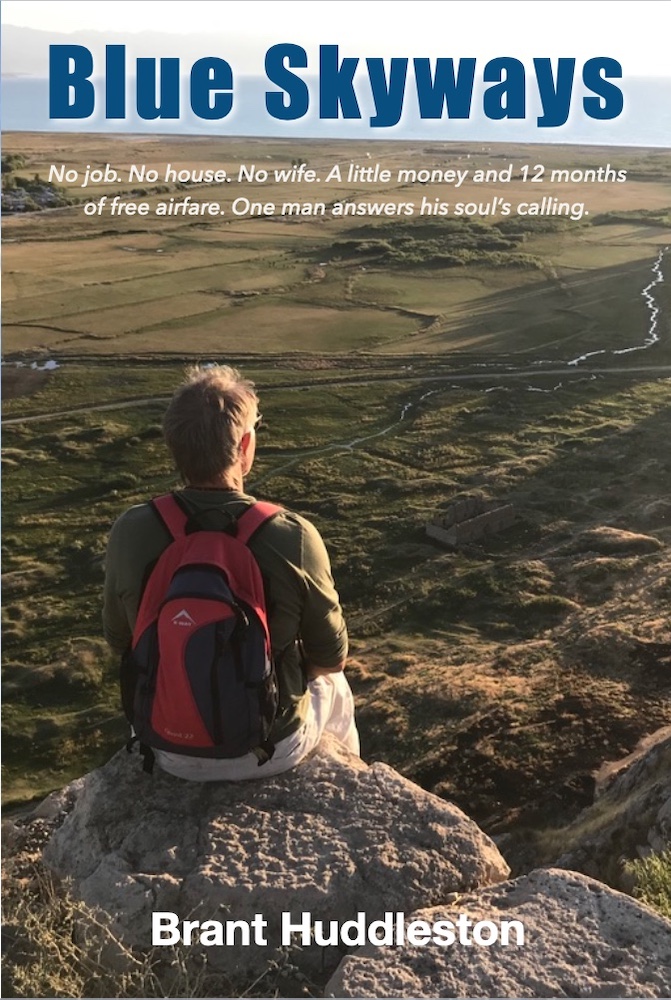

For Christmas 2018, my brother, a pilot with American Airlines, gave me a gift that became the experience of a lifetime: 12 months of free travel anywhere American Airlines flies.

Thus began a year long journey that took me from the rocky coasts of Portugal, to the hot sands of Morocco, to the mangrove swamps of Panama, with many places beyond and between. In cheap hostels and the backwaters of the nomadic milieu, I discovered a treasure chest of colorful and fascinating people. I tell their stories and a bit of my own.

The trip became as much a spiritual and emotional journey inward as it was a literal outward one, and found me in a place those of you who are in the second half of life are likely to recognize.

With references to the philosophies of Carl Gustav Jung, Jesus, Bob Dylan, and the Buddha, Blue Skyways is an international romp by a man in his 60’s with not much more than a pack on his back, and still much to learn.

A suspense/thriller novel!

When a psychology doctoral student Brian Drecker uses advanced software to analyze dreams from around the world, he discovers odd patterns that cannot be explained. Where one person's dream ends, another's begins. Unique objects appear again and again...even though the dreamers are complete strangers.

Drecker discovers the patterns form a map pointing to an ancient, lost object. Soon after, he is mysteriously murdered, leading his deadbeat brother and estranged wife on an international race to find the treasure, and the murderer. Along the way, the troubled couple are opposed by dark forces of the religious underworld, who launch a global pandemic to ensure the map of dream's secret remains lost forever.