Sebastian Page & the Unsung Heroes

Summary:

What does it mean to be really valuable to others? Does it mean creating something that has immediate market appeal? Is that the measure of our value, when we are lauded by our contemporaries and peers? If yes, then all of the unsung heroes whose remarkable ideas that made our modern life possible are abject failures. Since that does not ring true, I submit there is another way to think about it.

Below is a chapter from my third book Blue Skyways, in print and audio, read by me. Either way, I hope you enjoy it!

Sebastian Page & the Unsung Heroes

Don’t be trapped by dogma—which is living with the results of other people’s thinking. Don’t let the noise of others’ opinions drown out your own inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition.

Steve Jobs

I first met Sebastian at a hostel in Richmond, Virginia, where I was staying while helping my then 93-year-old mother recover from a serious fall. She was in the hospital with a broken clavicle and a fractured spine, and after attending to her needs, I would retire to the hostel, one of the nicest I have ever visited. The Richmond hostel’s kitchen is spacious, sunny, and sparkling clean, and I would make breakfast there every day before going to the hospital.

“Can I make you some scrambled eggs?” I asked Sebastian on my first morning. “It’s just as easy to make six as it is three,” I said.

“Are you sure you don’t mind?” Sebastian asked. I could tell by the accent, if not from his polite response, that I was dealing with a Brit.

Over eggs, coffee, and buttered toast, I learned Sebastian was in Richmond, the former capital of the Confederate States of America, to complete research on a project that had consumed 12 years of his life — the emigration of Americans after the Civil War and, specifically, the antebellum repatriation of African-American slaves to places outside the United States. That chapter of African-American history is one of America’s dark, dirty secrets, and Sebastian is about to blow the lid off when the results of his research are published.

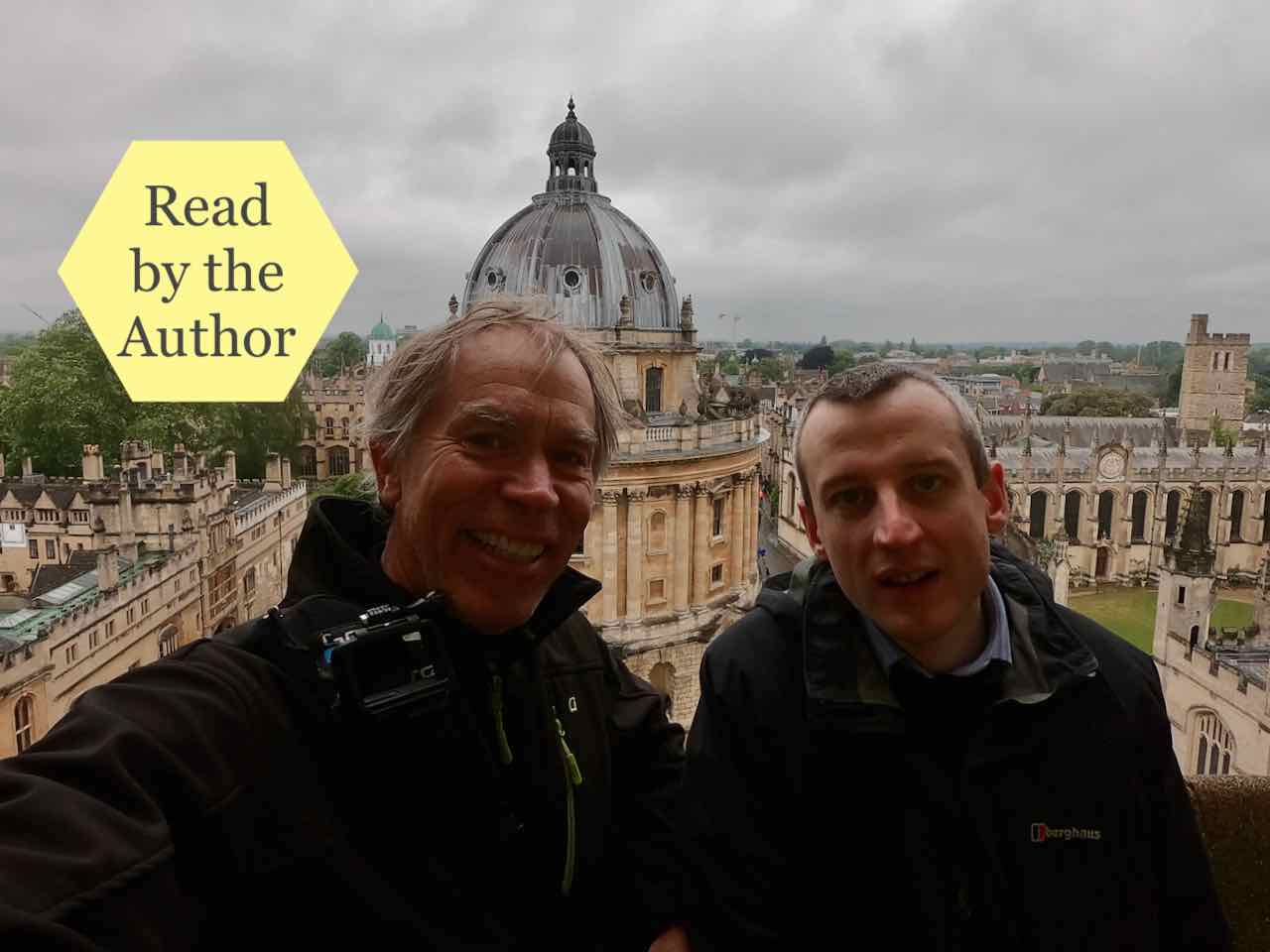

Please understand — Sebastian has no vendetta, no axe to grind, no dog in the fight between races. He is about as unassuming and unbiased as a gentleman can be. Standing 6’4” and 35 years of age, Sebastian Page is a lanky, Oxford University graduate who pretty much meets every stereotype a “Yank” like me thinks of that kind of character: tweedy, geeky, erudite, polite, and perfectly British. Oh, and one other thing — Sebastian is a heck of a nice guy!

During Sebastian’s final year as an undergraduate student at Corpus Christi College at Oxford, his advisor suggested Sebastian research this obscure and misunderstood niche of American history as a topic for Sebastian’s dissertation. With no better ideas, Sebastian latched onto the subject, thinking it would be a quick study of American slaves emigrating to Liberia, the African country politicians such as Abraham Lincoln initially scaffolded up as a dumping ground for solving the “Negro problem.” But that was just the tip of the dirty iceberg.

Guyana. Haiti. Brazil. Panama. In lands throughout Africa, Central and South America, and across the Caribbean, African-American slaves born in the U.S. were “encouraged” (pushed?) to move to those places in a U.S. government backed resettlement program. While the program had limited “success,” it allowed many of the original terrors of slavery to continue, tearing people from their homes, denying their rights, and breaking apart families. Even after Emancipation, black colonization continued to treat people like pieces of furniture that can be moved, rather than the divine humans they are. Abraham Lincoln, a man I otherwise greatly admire, was complicit.

Sebastian’s book is soon to be published, and I believe him when he says it will upset many historians who are satisfied with a more polite version of American history, and a more vaunted view of Lincoln. I am excited for Sebastian, and not only do I hope he sells a gazillion copies, I hope his 12 years of grueling research pays off in ways that can’t be measured in copies sold or dollars earned, but rather in the ultimate currency of a life well lived — a world transformed.

With his work on black emigration all but finished, Sebastian is more than ready to move on to a new field of study he expects to take him six or seven years to fully research. We had the opportunity to discuss his new interest during the visit I made to Oxford, just a short train ride from London. There I stayed at what is possibly the worst hostel I’ve ever visited. It was smelly, dirty, and over-crowded. Yuck.

“Oh God,” Sebastian said. “Please tell me you didn’t stay there, did you? It looks like some kind of halfway house for ex-convicts!”

“That would explain the surly looking characters lurking around the bathrooms,” I said.

But nothing blows the stink off a bad hostel like a pint or two of Fuller’s ESB, followed by a few pours of Scotch whisky, drunk in a quintessential British pub. Sebastian picked the place, and there we carried on a lively conversation with the bartender and the pub manager, about good whisky (Bunnahabhain for floral notes; Lagavulin for smoky. Just like licking the inside of a fireplace!), Brexit, and of course, Sebastian’s new passion — capital punishment.

“Oh yes,” he said to me over sips of beer, his eyes sparkling with enthusiasm. “The human brain continues to function some 20 seconds after decapitation.”

Hangings. Mutilation. Electrocution. Gassing. Every sort of ghastly way to legally kill humans comes under Sebastian‘s emerging field of expertise, girded by his careful research.

Did you know one American gas victim avoided death for 17 minutes by holding his breath? It’s true. I heard about it all while sipping whisky in a quaint British pub in Oxford, England.

Sometimes I think death is following me around like a shadow, but I am not that special. Death is everywhere, like air. It may seem invisible, until you think about it. Then you know he is there. We only pretend he isn’t.

***

I made one other call while in Oxford, to a U.S. citizen who relocated there with his family. Derek Sivers is loved and widely followed for his enlightened approach to business and life. In the early days of the Internet, long before Amazon, Derek, a musician, taught himself to program and built one of the first online systems for selling music CDs. Originally intending to sell only his own band’s CD, word spread among his friends and fellow musicians, and CDBaby was born — a business that Derek led to success and sold in 2008 for a tidy sum. The whole inspiring story is beautifully told in Derek’s book Anything You Want.

I originally “met” Derek via a well-read blog post he wrote a few years ago. In it, he implied that “we have the tendency to forget” the value of being “useful” when pursuing a fulfilling life. People who are “not useful,” he said, are those who fail to focus on “doing something that’s really valuable to others.”

In a far less-read response to Derek’s post, I challenged his assertion.

“What does it mean to be ‘really valuable’ to others?” I asked. “Does it mean creating something that has immediate market appeal? Is that the measure of our value, when we are lauded by our contemporaries and peers? If yes,” I said in my response, “then all of the unsung heroes whose remarkable ideas that made our modern life possible are abject failures.”

Who are some of those unsung heroes?

In his book How We Got to Now: Six Innovations That Made the Modern World, author Steven Berlin Johnson chronicles those who, in pursuit of a unique vision and widely disparaged by their contemporaries, doggedly pressed on toward a goal they alone could see, and upon achieving it, turned the tide of human history.

You are not likely to know their names, for they often died penniless and without acclaim. We only recognize the significance of their accomplishments in the revealing light of history. Here are just a few of those unsung heroes:

Ignaz Semmelweis, who was roundly mocked and criticized by the medical establishment when he first proposed, in 1847, that doctors and surgeons wash their hands before attending to their patients. It took almost half a century for basic antiseptic behaviors to take hold among the medical community, well after Semmelweis lost his job and died in an insane asylum.

Jean-Baptiste-Ambroise-Marcellin Jobard, a 19th Century Belgian who experimented with artificial electric light 150 years before Thomas Edison, the American who gets all the credit for inventing the light bulb.

Charles Vernon Boys, “one of the worst teachers who has ever turned his back on a restive audience,” and the 19th century inventor of glass thread, the core material in what we know as fiber-optic cable, which is today the backbone of the global Internet.

Then there is Ada Lovelace, a 19th century English mathematician and writer known for her work on Charles Babbage’s early mechanical general-purpose computer, the Analytical Engine. Her notes on the engine include what is recognized as the first algorithm intended to be carried out by a machine, that is, a computer program.

The obstacles against Ada were many, not the least of which she was a woman in Victorian England. Any student of history knows that alone was enough to keep her down. But she overcame, arguably becoming the first computer programmer nearly 100 years before the computer, as we know it, was even invented. Even with my 30 years in the software industry, I had never heard of Ada Lovelace until Mr. Johnson recognized her accomplishments in his book, in which I found this superior description of value in its closing lines:

There is comparable risk in being true to your own sense of identity, your own roots. Better to challenge those intuitions, explore uncharted terrain, both literal and figurative. Better to make new connections than remain comfortably situated in the same routine.

If you want to improve the world slightly, you need focus and determination; you need to stay within the confines of a field and open the new doors in the adjacent possible one at a time. But if you want to be like Ada, if you want to have an “intuitive perception of hidden things”—well, in that case, you need to get a little lost.

Derek and I chose not to continue our debate when we met for coffee in Oxford, rather, we enjoyed an easy-going conversation about friends, family, and new ideas. Derek was friendly, gracious with his time, and genuinely curious about my life and travels. I look forward to building my friendship with him, as I do with Sebastian.

My two Oxford friends, one sung, the other unsung (but about to be) — both good men. Meeting them made for a fine day. The only thing that tried to take the shine off was the sour smell of unwashed armpits in my stuffy hostel room that night, surrounded by 17 other male bodies exhausting gas from one end or the other, and an ex-convict breathing hard in the creaky cot above me.

###

Other Unsung Heroes

“This ‘telephone’ has too many shortcomings to be seriously considered as a means of communication. The device is inherently of no value to us.” Western Union internal memo, 1876.

“The wireless music box has no imaginable commercial value. Who would pay for a message sent to nobody in particular?” David Sarnoff’s associates in response to his urgings for investment in the radio in the 1920s.

“A cookie store is a bad idea. Besides, the market research reports say America likes crispy cookies, not soft and chewy cookies like you make.” Response to Debbi Fields’ idea of starting Mrs. Fields’ Cookies.

“We don’t like their sound, and guitar music is on the way out.” Decca Recording Co. rejecting the Beatles, 1962.

“The concept is interesting and well-formed, but in order to earn better than a ‘C,’ the idea must be feasible.” A Yale University management professor in response to Fred Smith’s paper proposing reliable overnight delivery service. (Smith went on to found Federal Express Corp.)

“Who the hell wants to hear actors talk?” H.M. Warner, Warner Brothers, 1927.

“Heavier-than-air flying machines are impossible.” Lord Kelvin, president, Royal Society, 1895.

“If I had thought about it, I wouldn’t have done the experiment. The literature was full of examples that said you can’t do this.” Spencer Silver on the work that led to the unique adhesives for 3-M “Post-It” Notepads.

“So we went to Atari and said, ‘Hey, we’ve got this amazing thing, even built with some of your parts, and what do you think about funding us? Or we’ll give it to you. We just want to do it. Pay our salary, we’ll come work for you.’ And they said, ‘No.’ So then we went to Hewlett-Packard, and they said, ‘Hey, we don’t need you. You haven’t got through college yet.’” Apple Computer Inc. founder Steve Jobs on attempts to get Atari and H-P interested in his and Steve Wozniak’s personal computer.

“Professor Goddard does not know the relation between action and reaction and the need to have something better than a vacuum against which to react. He seems to lack the basic knowledge ladled out daily in high schools.” 1921 New York Times editorial about Robert Goddard’s revolutionary rocket work.

“You want to have consistent and uniform muscle development across all of your muscles? It can’t be done. It’s just a fact of life. You just have to accept inconsistent muscle development as an unalterable condition of weight training.” Response to Arthur Jones, who solved the “unsolvable” problem by inventing Nautilus.

“Drill for oil? You mean drill into the ground to try and find oil? You’re crazy.” Drillers who Edwin L. Drake tried to enlist to his project to drill for oil in 1859.

“Stocks have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.” Irving Fisher, Professor of Economics, Yale University, 1929.

“I’m just glad it’ll be Clark Gable who’s falling on his face and not Gary Cooper.” Gary Cooper on his decision not to take the leading role in “Gone With The Wind.”

“Computers in the future may weigh no more than 1.5 tons.” Popular Mechanics, forecasting the relentless march of science, 1949

“I think there is a world market for maybe five computers.” Thomas Watson, chairman of IBM, 1943

“I have traveled the length and breadth of this country and talked with the best people, and I can assure you that data processing is a fad that won’t last out the year.” The editor in charge of business books for Prentice Hall, 1957

“But what … is it good for?” Engineer at the Advanced Computing Systems Division of IBM, 1968, commenting on the microchip.

“There is no reason anyone would want a computer in their home.” Ken Olson, president, chairman, and founder of Digital Equipment Corp., 1977

“Airplanes are interesting toys but of no military value.” Marechal Ferdinand Foch, Professor of Strategy, Ecole Superieure de Guerre.

“Everything that can be invented has been invented.” Charles H. Duell, Commissioner, U.S. Office of Patents, 1899.

“Louis Pasteur’s theory of germs is ridiculous fiction”. Pierre Pachet, Professor of Physiology at Toulouse, 1872

“The abdomen, the chest, and the brain will forever be shut from the intrusion of the wise and humane surgeon”. Sir John Eric Ericksen, a British surgeon, appointed Surgeon-Extraordinary to Queen Victoria 1873.

“640K ought to be enough for anybody.” Bill Gates, 1981

###

Books by Brant

Most Recent

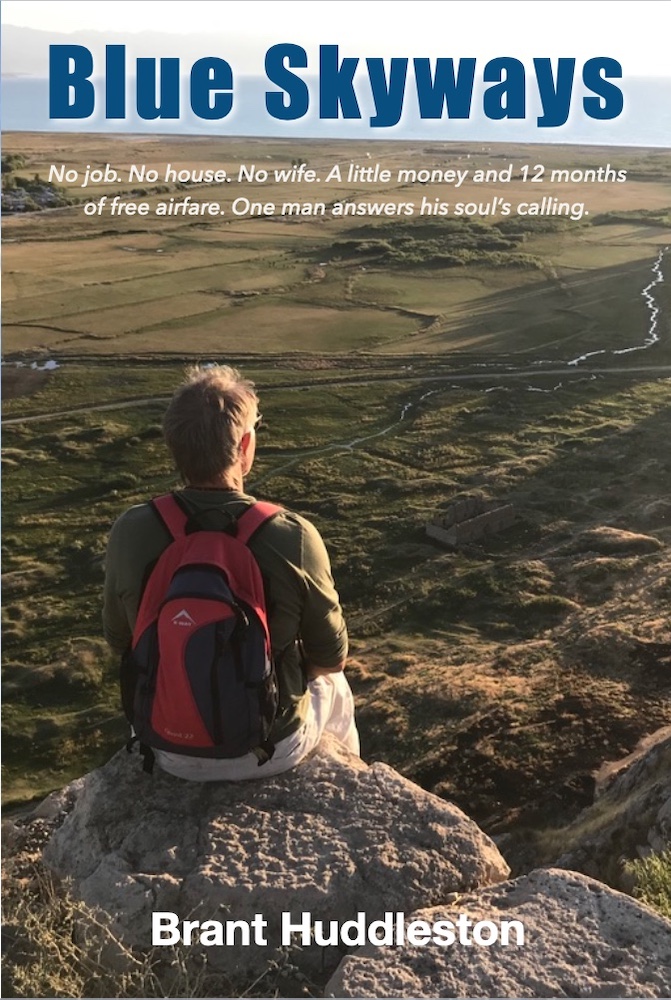

For Christmas 2018, my brother, a pilot with American Airlines, gave me a gift that became the experience of a lifetime: 12 months of free travel anywhere American Airlines flies.

Thus began a year long journey that took me from the rocky coasts of Portugal, to the hot sands of Morocco, to the mangrove swamps of Panama, with many places beyond and between. In cheap hostels and the backwaters of the nomadic milieu, I discovered a treasure chest of colorful and fascinating people. I tell their stories and a bit of my own.

The trip became as much a spiritual and emotional journey inward as it was a literal outward one, and found me in a place those of you who are in the second half of life are likely to recognize.

With references to the philosophies of Carl Gustav Jung, Jesus, Bob Dylan, and the Buddha, Blue Skyways is an international romp by a man in his 60’s with not much more than a pack on his back, and still much to learn.

A suspense/thriller novel!

When a psychology doctoral student Brian Drecker uses advanced software to analyze dreams from around the world, he discovers odd patterns that cannot be explained. Where one person's dream ends, another's begins. Unique objects appear again and again...even though the dreamers are complete strangers.

Drecker discovers the patterns form a map pointing to an ancient, lost object. Soon after, he is mysteriously murdered, leading his deadbeat brother and estranged wife on an international race to find the treasure, and the murderer. Along the way, the troubled couple are opposed by dark forces of the religious underworld, who launch a global pandemic to ensure the map of dream's secret remains lost forever.