My Greatest Failure, or How to Love Someone to Death

Be certain

in the religion of Love

there are no

believers or unbelievers

Love embraces all.

Rumi

On the day I wrote the following essay, I was awakened not by a dream, but more like a powerful feeling. I knew instantly what it meant ~ that in his dying hour I had completely failed my brother John.

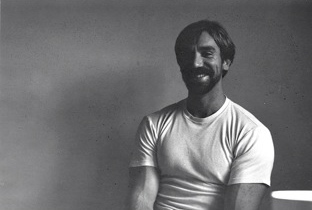

For those who don’t know, my brother died in 1992 from complications arising from HIV and hepatitis. He was 39 years old, a single man, childless, and just starting a new career. I was 37 then, a young father and a busy professional.

That was then. Now I am in my 60’s, and my feelings about John’s death, and my role in it, have changed dramatically. The essay below is a chapter from my book Blue Skyways. My hope is that by sharing what I learned, others might avoid my mistake.

My Greatest Failure, or How to Love Someone to Death

For years I proudly believed that my last conversation with John, where it was just the two of us in his dark hospital room, was one of the high points of my life. In that moment I said, “You know John, this may be your last chance to accept Jesus Christ as your Lord and Savior. Do you?”

His eyes were closed, his body immobile. He had been silent up until then, weakened by the disease, but to this particular interrogation, his feeble response was, “Whatever you say, Brant.”

Those were the last words I ever heard from John. I left the room rejoicing. I got what I came for — his salvation. Although his answer was tepid, it was enough, I believed, for a gracious God to allow my brother into heaven. “If you have faith as small as a mustard seed,” Jesus said, “you can move mountains.” John’s answer, as small as it was, would do the job. I was satisfied.

That moment was, for many years, my greatest accomplishment as an evangelical Christian. I had saved my brother. Now, looking back, I consider it to be one of my greatest failures as a human being.

Consider this.

Here is a man, for the most part alone in a hospital bed (a cheap one at that), surrounded by people who did not know or really care that it was to be his last night on earth. His liver had failed, and he was being poisoned to death by his own body. His legs were swollen like tree trunks. The government, caught off-guard by the HIV epidemic, was using my brother as a human lab rat for an experimental drug that eventually failed. I can only imagine now how shitty and lonely and scared he must have felt.

And where was I? There like a salesman wanting to put another notch on my evangelical six-gun handle, and having gotten it, getting the hell out of that room.

Oh, how I long now to do it over, not to leave, but to stay by his side, telling stories from our childhood down by the Severn River in Maryland: swimming out to the floating dock in the warm days of summer, racing our sleds down Severnside Drive and onto the ice, making our own Halloween costumes (he was fantastic at it) and bringing home shopping bags full of candy, remembering the sweet taste of white traubenzucker candy we would buy at the store across the street from our tiny house in Germany, of hunting starfish off Cape Cod, of the time I visited him in the Castro, when it was still terrifying for a gay man to come out, but he did.

John loved the B-52s. Why not play him some of his favorite music? Why not stay? What was I thinking?

The fact is, I wasn’t thinking, and worse, I wasn’t feeling either. At that time in my life, I sorely lacked empathy, a personal shortcoming that would contribute to my unhappy marriage and divorce a few years later. Although I understood intellectually that the highest calling of my Christian faith was to love, I didn’t practice it that way. As an Evangelical, the highest calling of my Christian faith was to win souls — an egregious misunderstanding of Jesus’s teachings. How much more love I would have demonstrated had I gone to the hospital that night, prepared to do everything in my power to help John’s transition from life to death to be as comforting and kind as possible. It needed to be all about him that night, not me, and I failed him. I was given a rare, literally once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to love someone to death, and I missed it.

Eventually, one way or the other, we will all have our own encounter with death. It does not belong to an exclusive club of industry insiders or an order of so-called “deathies” who possess some secret knowledge unavailable to the rest of us. Unlike birth, the experience of which belongs only to women (babies don’t remember, but women never forget), death knows no gender. It knows no race…no ethnicity…no title or position. Death is purely unbiased. It visits us indiscriminately. Death, perhaps more than anything else, like air, belongs to all of us.

In a sense, we have an obligation as human beings not to avoid death, for to do so is to avoid preparedness for the inevitable, which is insanity. Had I been more prepared, more thoughtful about death, I am confident I would have made John’s journey a better one. Then perhaps I would’ve shown up with a cassette tape of the B52’s “Rock Lobster”, a taste of traubenzucker, a beeswax candle, his treasured dinosaurs and Buddha head, and different words, not about his eternal destination, which is the sovereign ruling of the gods, but ones that might have helped him take the first few uncertain steps ahead, into the unknown.

I love you John. I’m so happy to be here with you. I’m not leaving. Would you like to hear some stories from our childhood? Would you like to hear some B-52’s, or sounds of the ocean? I have some traubenzucker — would you like a taste? Is there anyone I can call for you? Would you like to hear about summer days down by the Severn river?

That would have been love.

###

More about John

For another personal essay on how John’s death affected me, see “The Mystery of the Coffee Grinds.”

To learn how John’s death influenced my decision to start a podcast on death, see “A Path to Your Own Treasure.”

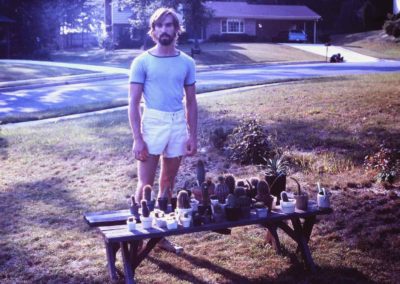

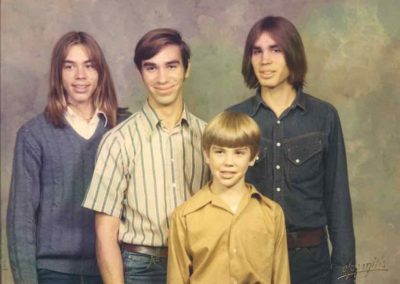

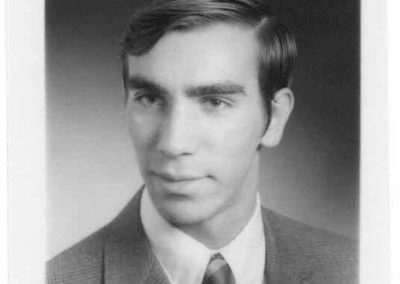

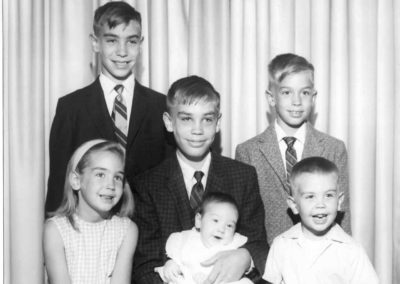

Below are also some pictures of my brother, alone or with our family of six kids (youngest not shown).

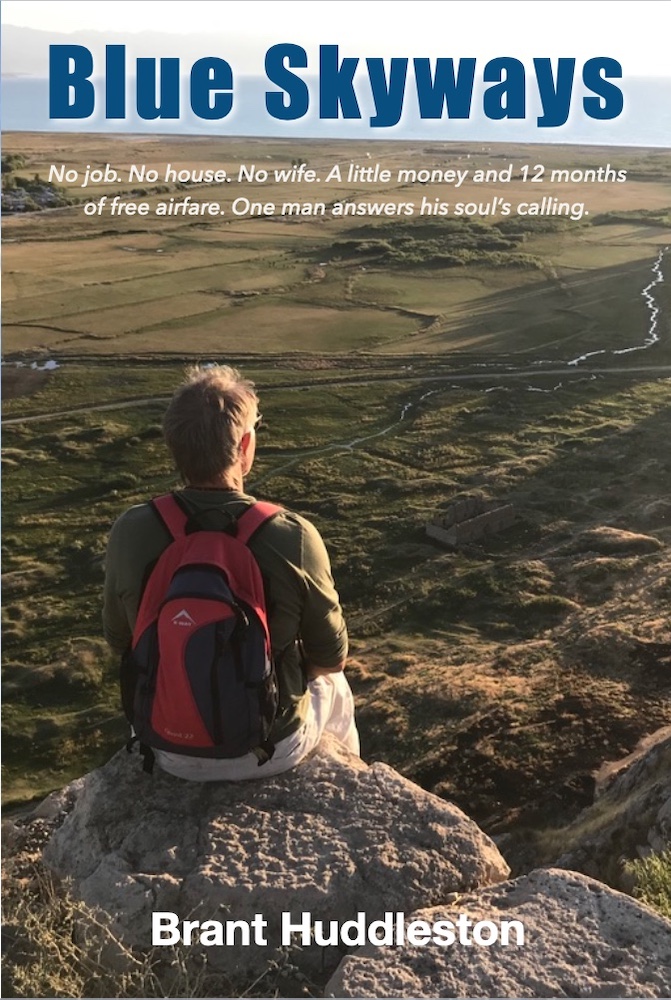

Books by Brant

Most Recent

For Christmas 2018, my brother, a pilot with American Airlines, gave me a gift that became the experience of a lifetime: 12 months of free travel anywhere American Airlines flies.

Thus began a year long journey that took me from the rocky coasts of Portugal, to the hot sands of Morocco, to the mangrove swamps of Panama, with many places beyond and between. In cheap hostels and the backwaters of the nomadic milieu, I discovered a treasure chest of colorful and fascinating people. I tell their stories and a bit of my own.

The trip became as much a spiritual and emotional journey inward as it was a literal outward one, and found me in a place those of you who are in the second half of life are likely to recognize.

With references to the philosophies of Carl Gustav Jung, Jesus, Bob Dylan, and the Buddha, Blue Skyways is an international romp by a man in his 60’s with not much more than a pack on his back, and still much to learn.

A suspense/thriller novel!

When a psychology doctoral student Brian Drecker uses advanced software to analyze dreams from around the world, he discovers odd patterns that cannot be explained. Where one person's dream ends, another's begins. Unique objects appear again and again...even though the dreamers are complete strangers.

Drecker discovers the patterns form a map pointing to an ancient, lost object. Soon after, he is mysteriously murdered, leading his deadbeat brother and estranged wife on an international race to find the treasure, and the murderer. Along the way, the troubled couple are opposed by dark forces of the religious underworld, who launch a global pandemic to ensure the map of dream's secret remains lost forever.